|

Peak Oil and India

Are we scraping the bottom

of the barrel? Despite the Big Oil bravado, energy gurus actually

believe the world might be nearing Peak Oil - The End of Cheap

Gasoline.

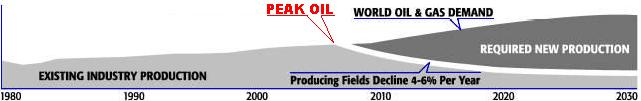

Peak oil is the point at which

about half the oil reserves in the world have been produced.

Peak oil is not the end of oil. It is the end of cheap oil.

After peak oil is reached the

production will reverse the momentum and will start to slowdown.

Estimates put this figure in the range of 4-6% per annum,

where as the demand will still continue to grow amid the growing

economy and industrialization. This will create an energy

void throwing the oil prices further north and causing double

sided damage to the growth - one due to high price of oil

and other due to its gradual increase in scarcity.

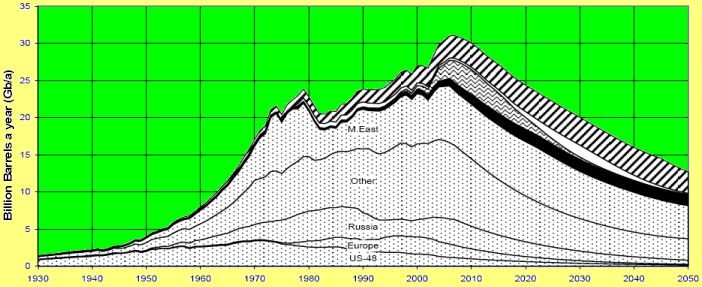

When will the peak of world

oil production come is much debated topic and various experts

provide various dates ranging from the year 2000 to 2020.

Currently most accepted date is in the vicinity of 2010.

Mr. Simmons

may be a much hated man in the Big Oil World but there is

no denying that his views on the global oil scenario is increasingly

gaining ground and this surely has got oilmen worried. He

has been one of the key advisors on energy to the Bush administration

which is now turning around to making "Powering Down"

its mantra. Policy makers across the world are grudgingly

coming around to Mr. Simmon's view that this time around the

peak oil scare is for real.

But is the world ready to bite the bullet?

Big Oil believes that there is enough oil going to meet the

energy hungry nations. Says Sue Payne, planning manager (exploration),

Exxon Mobil: "An estimated 2.2 trillion barrels of oil

still remains as reserves worldwide, compared to the 1 trillion

barrels already extracted. And this does not include shale

oil, oil sands and extra heavy oils, which is pegged at another

1 trillion barrel." New technology - injecting water

or carbon dioxide, horizontal drilling - should be able to

siphon more oil out of old oil fields, amounting to 10-15%

of what was initially recovered.

Frontier technologies are being employed

to produce tar oil or shale oil even as gas to liquid are

being considered as an option. Others like British Petroleum

believe that the existing fields have more reserves than what

is shown. In fact, advanced seismic technologies should yield

better reserve results.

But this is exactly what Simmons questions.

"I think the three groups together along with Exxon Mobil

and BP have been responsible for a drumbeat of publicity that

has basically convinced a lot of people in the world that

we really don't have any energy problems. They basically have

to live in the world they created which was an illusion."

The data available on oil productivity is

sketchy as little is devolved on field by field production.

There is no public information on the historical decline rates

of most producing fields. Proven reserves are commingled on

a company by company basis or lumped together under an entire

country so breaking down the reserves into high quality light

oil instead of low quality heavy oil is impossible to even

guess at, analysts say.

Oil companies, however, have a completely

different take. It is claimed that data collated over the

years has only improved with better technology and they are

now in a better position to assess the hydrocarbon reserves.

Yergin had till recently quoted a comprehensive field by field

study which projected an addition of 16.4 million barrels

a day of new oil capacity being created. But Mr. Simmons counters

that "it's not a very good piece of work and the odds

of that happening are about as high as having a subdivision

on Mars by 2010."

And even as the world at large

continues to debate over whether we have reached peak oil,

global oil prices have managed to remain northward bound for

more than a year defying every economic logic. Blame it on

the growing demand by China, US and India or the increasing

geopolitical tensions in Iran, Asia Pacific region or Africa.

There is no escaping the high oil prices and a global crude

price of $100 a barrel is no longer an outrageous thought.

Energy guzzling economies like the US are

beginning to feel the pinch of high oil prices. At pump prices

moving to $3 a gallon, economists at IAEA feel demand elasticities

would soon set in. A similar thought is echoed by Wang Zhonghong

in the Development Research Centre in the state council of

PRC. "Consumers are moving in for lower grades of fuel

I would move onto grade 93 which is a cheaper fuel. And in

the long run high fuel prices will impact car usage patterns."

Retail prices were hiked by over 25% this year alone, although

it is still 35% cheaper than US retail prices.

Demand drivers like India have opted for

a more political option. In what may seem as a complete paradox,

consumers in India pay the highest fuel price in the Asia

Pacific region even though oil companies bleed. Simple, the

government pockets almost 50% of the sale price as taxes even

as it doles out huge subsidies in the federal budget.

But the truth on peak oil and its impact

on prices would probably be more in the grey than black and

white. Says Lane Sloane at the Global Energy Management Institute

at Houston: "Peak oil is certainly a raging debate which

happens every time crude oil prices rise rapidly because of

current low spare production capacity. We know for sure that

oil is a depletable resource and we know that oil has already

peaked in some countries such as the United States. The Hubert's

curve people are claiming it will peak globally within this

decade while others envision technology and man's innovation

will bring us to Robert Mabro's observation that "the

Stone Age did not end for lack of stones."

Bio Fuel

Bio-fuel, it's a bubble looking for the first

prick. Yes, the world over, governments are doling out billions

of dollars as subsidies to secure an alternative sustainable

source of energy, but questions are already beginning to crop

up on the cost effectiveness and the energy efficiency of

these solutions.

While countries like Brazil have taken the

lead and have brought in the ethanol revolution, others like

US are looking at corn/soya solutions while India is banking

upon its sugarcane-based ethanol for its gasoline doping program.

And the search for alternatives is not just about cane or

Soya British Petroleum recently launched tallow blended diesel

oil for the Australian market. Although, on an experimental

basis, the company has put in place facilities in one of its

refineries in Australia to blend the tallow from Australian

sheep with crude and produced blended fuel.

But even as this may come as a fancy innovative

solution, this is at best a local answer to existing oil crisis.

Bio-fuels are expected to play only a small part in substituting

for oil, perhaps not more than 10% and possibly as high as

20% with major environmental impacts.

And myth-busters like David Fridley, scientist

at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, have this to

say on bio-fuels: "This will fulfill a market niche in

the near-term, but long-term potential is low. Also large-scale

bio-fuel production is environmentally destructive and more

importantly bio fuel production impacts food security. Cellulosic

technology creates the same problems as grain-based technology

and most of all bio fuels will drain investment away from

other appropriate alternatives."

Related Story

India Can't Produce Enough Ethanol As Most Of The Cane Is

Required For Producing Sugar

Hydrogen & Fuel Cell

Here's Mr. Fridley on hydrogen: "Hydrogen

is a myth. It is an energy carrier, not an energy source,

and thus must be made from another form of energy." This

may be highly contested by leading automakers like Toyota,

Ford or Daimler Chrysler who have been pumping in huge investments,

albeit with large doles from the US government, in collaboration

with the big oil guys, to develop those fancy hydrogen cars.

Proponents say hydrogen can be made with

renewable energy, but since renewable energy is approximately

1% of world energy, and oil is about 1/3rd, you could end

up losing energy both in the production of hydrogen, in its

transport, and then in its use in vehicles.

The government appears to have divergent

views on the fallout of high oil prices on the country's economic

growth. The Planning Commission has opted for a cautious view

and has warned that high oil price may have an impact on the

growth rate, even as the finance ministry maintains that rising

oil prices are unlikely to impact GDP.

"In a high oil price scenario, our growth

rate could be lowered by between 0.5 and 1.0 percentage points

below our normal potential," the Planning Commission

said in the draft approach paper of the 11th Five-Year Plan.

According to its assessment, oil prices are expected to remain

high and it will "exert contractionary pressure on the

economy, both directly and also through their impact on world

economic growth".

The finance ministry, however, has a different

view on the issue of fuel price hike and its impact on GDP

growth. Commenting on the country's revised annual estimates

on May 31, 2006, finance minister P Chidambaram said if oil

prices rose and if it was reflected in domestic prices, it

would have an impact on inflation. "Rise in oil prices

worldwide need not affect growth rate," he had said.

The revised annual estimate records 8.4%

GDP growth in 2005-06, surpassing the advance estimate of

8.1%. The growth has been significantly high compared to previous

year's figure of 7.5%.

While the finance ministry's views may hold

some ground given the demand elasticity of the product, countries

across the world are now coming around to the view that it

would impact GDP if global prices continue to be northward

bound.

The Planning Commission has, however, suggested

that the adverse impact of high oil prices on GDP growth can

be substantially moderated in the medium term by "appropriate

oil pricing policies, increased exports and appropriate fiscal

and monetary policies.

The approach paper suggests a long-term solution:

"The only viable policy to deal with high international

oil prices is to rationalise the tax burden on oil products

over time, remove fat which may exist in existing pricing

mechanisms which give the oil companies as excessive margin,

realise efficiency gains through competition at the refinery

gate and retail prices of petroleum products, and pass on

the rest of the international oil price increase to consumers,

while compensating targeted groups below the poverty line

as much as possible."

It has suggested that the government reconsider

the current method of determining prices for petroleum products

on the basis of import parity. "India is deficient in

crude oil but has developed surplus capacity in products.

Product price entitlement should, therefore, be based on export

parity pricing, which would be much lower than import parity,"

it said.

It has suggested to further reduce the duty

on petroleum produced by 5% to equate it with the duty on

crude. The 10% duty on products has recently been reduced

to 7.5%.

Stating that the increase in oil prices is

now expected to persist for some years, the paper said, "Although

prices of some petroleum products have been raised, the increase

still leaves a large uncovered gap." It has said that

the gap was partly being borne by the oil companies and partly

by the issue of bonds, which was equivalent to a government

subsidy. According to the draft approach paper, consumption

of petroleum products is likely to rise from 112 mt in 2005-06

to about 135 MT by the end of the 11th Plan, with net crude

oil imports reaching 110 Mt.

The Republic of India covers an area of some

3M sq km, making it the seventh largest country in the World.

Topographically, it is divided into a mountainous north, flanking

the Himalayan Range; the North Indian Plain, drained by the

Indus and Ganges Rivers; and the Deccan Plateau in the south,

which itself is flanked by the Western and East Ghat mountain

ranges, locally rising to around 3000m. Its climate is characterised

by three seasons: hot and wet from June to September; cool

and dry from October to February; and hot and dry from February

to June. But they are subject to marked annual variations,

spelling famine if the rains are late or weak, or flooding

in the opposite case. Much of the country is forested.

India (which included Pakistan prior to 1948)

has had a very long history, with the earliest records of

the Indus Civilisation going back more than 4000 years. That

was followed by the so-called Aryans, so admired by the Nazis,

who spread out from Central Asia to populate India as well

as Europe and intervening territories. Later, came Greek,

Roman, Arab and Turkish influences, and the growth of sundry

kingdoms, whose fortunes waxed and waned with the passage

of history. The people enjoyed an advanced culture embracing

many religions, principally Buddhism, which itself evolved

and split into diverse sects. Arab invasions and raids brought

the Muslim faith particularly to northern and western India

from the 12th Century onwards. The great Mughal Empire, lasting

for 200 years from 1526, effectively unified the sub-continent,

bringing an age of affluence and stability, as well as the

growth of trade with Europe, but it finally disintegrated

with conflicts between the nobility. The Portuguese navigator

Vasco da Gama had landed in 1498, paving the way for the establishment

of Goa as a Portuguese territory. The Dutch and French also

had a presence, but it was the British who finally made India

the jewel of their Empire. British influence started with

the East India Company that secured a trade monopoly in 1600,

and later demanded military and political support, becoming

an early kleptocracy as its functionaries amassed great wealth.

Tea plantations were established in the early 19th Century,

especially in the hill country of Assam, becoming a major

source of export earnings, as Europeans developed a taste

for it. British control was achieved gradually by a series

of alliances with the separate principalities making up the

country as well as through military engagements (one notable

General was named Sir Colin Campbell). The pinnacle of British

power came in the latter part of the 19th Century, and seems

to have enjoyed wide support from the people at large. Indian

regiments under British officers were raised, playing heroic

parts in the both World Wars. But stirrings of independence

developed in the early 20th Century, receiving some sympathy

in the mother country. The movement was led by Mahatma Gandhi

(1869-1948), who preached tolerance and non-violence. The

eclipse of the British Empire in the Second World War and

the ensuing socialist regime paved the way for Indian independence,

which was granted in 1947. It saw the partition of the country

into mainly Hindu and Muslim territories, the latter becoming

Pakistan, but it cost the lives of more than a million people

in various factional massacres. The new government, led by

Mr. Nehru, faced a continuation of communal conflict resulting

from partition and economic dislocation, to be soon followed

by the outbreak of an undeclared war with Pakistan over the

status of Kashmir, with its predominantly Muslim population,

which found itself on the other side of the dividing line.

India has not proved to be an easy place

to govern. Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi, came to power

after the death of her father. She proved to have an iron

will and an autocratic style, taking a non-aligned position

between the opposing powers in the Cold War, but was shot

dead in 1984 by two Sikh guards following a dispute with the

Sikh minority. She was succeeded by her son Rajiv, who was

in turn assassinated by a Tamil suicide bomber in 1991. His

Italian-born widow, Sonja (Sonia in India), might have come

to power recently with adequate political support, but perhaps

wisely stepped aside for the present incumbent, Manmohan Singh,

a gentle economist, educated at both Oxford and Cambridge.

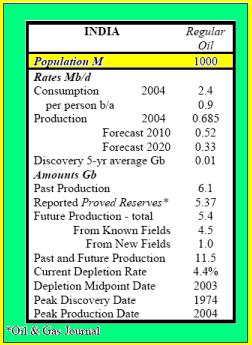

In geological terms, India forms a segment

of the ancient southern continent of Gondwanaland that moved

northwards to collide with the Eurasian Plate some 50 million

years ago. In regional terms, this continent was deficient

in oil prospects, primarily because the conditions for oil

generation were restricted in high southern latitudes. It

is not surprising, therefore, that India is not rich oil territory,

although some marginal basins have delivered modest results.

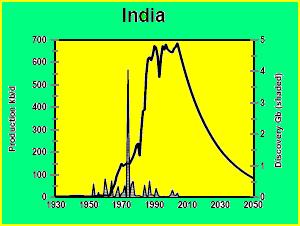

The largest of these, with some 2.5 Gb, is the Bombay High,

off the west coast, which was found in 1974. The industry

is dominated by the State Company, ONGC, although some small

foreign private firms are also active. About 1300 wildcats

have been drilled, finding 10.5 GB of oil, of which 6 GB have

been produced. Exploration drilling peaked in 1991 when 88

wildcats were drilled, but is now down to about half that

number. A fairly high level of activity is likely to continue,

as the country is in desperate need of oil, but is unlikely

to be rewarded by more than perhaps another billion barrels,

mainly in small fields. Some interest is now being devoted

to deepwater possibilities, but the outcome is far from assured.

Production stands at 685 kb/d, which is likely

to be the peak, the midpoint of depletion having been passed

in 2002. At the current Depletion Rate of 4.4%, production

is set to fall to about 500 kb/d by 2010 and 330 kb/s by 2020.

Consumption stands at 2.4 Mb/d, giving the country a large

and growing need of imports, which will be increasingly difficult

to obtain. This readily explains why State-backed Indian companies

are taking up rights overseas in for example the Sudan, Libya,

Iran and Venezuela (see also Items 511 and 513).

The country's gas potential is also limited.

Only 42 Tcf have been discovered, of which 13 Tcf have been

produced. Production stands at about 2 Tcf/a. The country

has substantial coal deposits, although some have a high arsenic

content which has caused serious environmental damage in the

past. India has recently enjoyed something of an economic

boom, based in part on services run through the Internet.

Western manufacturers have also set up to benefit from cheap

labour. It is however likely to be a short-lived chapter of

relative prosperity, as imported energy becomes at first expensive

and then in short supply. An economic downturn will likely

impinge on an already fragile political structure, rendered

even more difficult by the country's huge population of more

than a billion. How India will fare during the Second Half

of the Oil Age is hard to predict, but disintegration is a

possible outcome, as people revert to their old communal and

religious identities, a process which will probably be accompanied

by much bloodshed and suffering. Clearly, the present population

far exceeds the carrying capacity of the land, but the Indian

is blessed by a smiling, benign spirituality that helps.

»

Continued on the Next Page - Oil Crisis

Last Updated

28 July 2006

|